The case for Labour making an electoral pact

There’s a lot of water to flow under the bridge before the next general election. The future of Scotland and potential boundary changes are just two issues that would change the dynamics. Nevertheless, this piece assesses the potential for opposition parties and their voters working together to deny the Conservatives a majority at the next election. The data behind the analysis can be found here.

Tactical voting is an established part of our first past the post electoral system. For the most part it is done by those who want to vote against the Conservatives, though it has also been a feature of pro-unionist voting in Scottish elections.

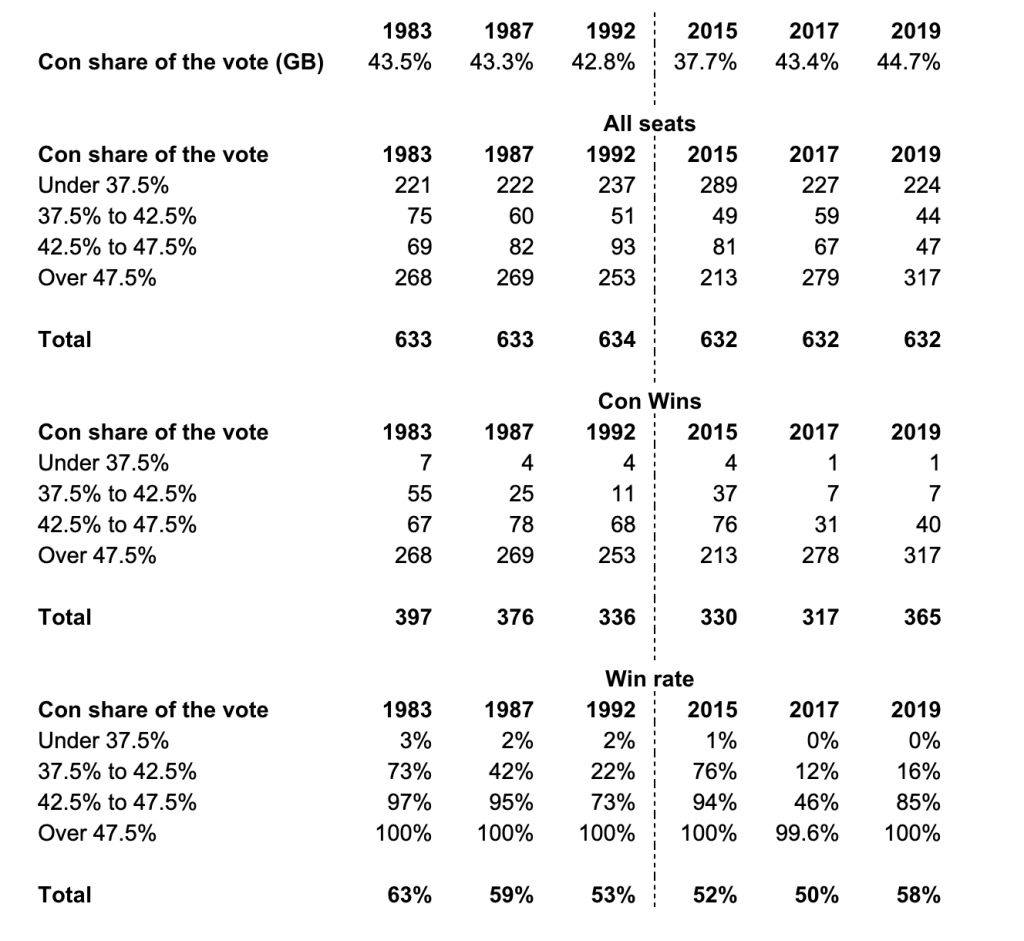

How much scope is there for the Conservatives to lose seats simply through the tactical voting? The table below splits the GB seats into four categories based on the Conservative share of the vote in six general elections (1983 to 1992 and 2015 to 2019). It’s worth noting that only once since 1983 have the Tories lost a seat when getting more than 47.5% of the vote. That was Newcastle-under-Lyme (48.1%) in 2017, the general election when the combined Conservative and Labour vote broke 80% for the first time since 1979.

The split opposition in 1983 gave Margaret Thatcher a comprehensive victory with 43.5% of the vote. The Tories even managed to win seven seats with less than 37.5% of the vote. Over the next two elections, tactical voting resulted in the Tories losing 61 seats despite their share of the vote falling by only 0.7 points. Having won 73% of seats in which they achieved 37.5% to 42.5% of the vote in 1983, the Conservatives won only 22% of seats with that vote share in 1992.

David Cameron achieved similar win rates in 2015 to those of Margaret Thatcher in 1983 as anti-Tory tactical voting broke down. However, Theresa May in 2017 and Boris Johnson in 2019 were much less successful in the 37.5% to 42.5% bracket. In short, there is not much low hanging fruit for the opposition parties.

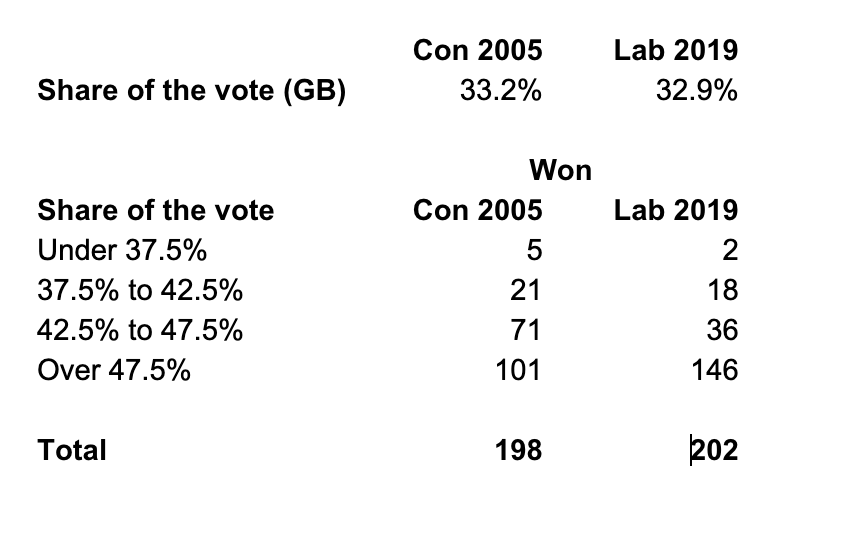

As a measure of how Labour’s vote has become concentrated in metropolitan areas, look at how their 2019 performance compares with that of the Tories in 2005. In 146 out of 202 seats (72%) won by Labour in 2019, they did so with over 47.5% of the vote. By contrast, the Tories in 2005 achieved that level of support in just over half of their 198 seats.

Don’t forget about the Brexit Party

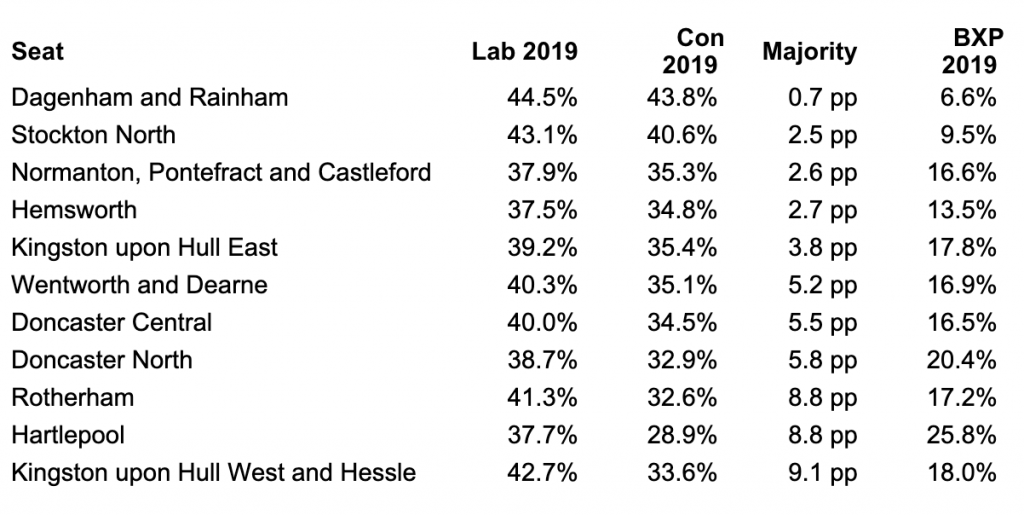

And it gets worse for Labour. The Brexit Party fielded candidates in seats not won by the Conservatives in 2017. Assumptions about the Tories cleaning up the 2015 Ukip vote proved overly optimistic in 2017. The result of the Hartlepool by-election, however, suggests that the Tories may find it easier to cannibalise the Brexit Party vote at the next election.

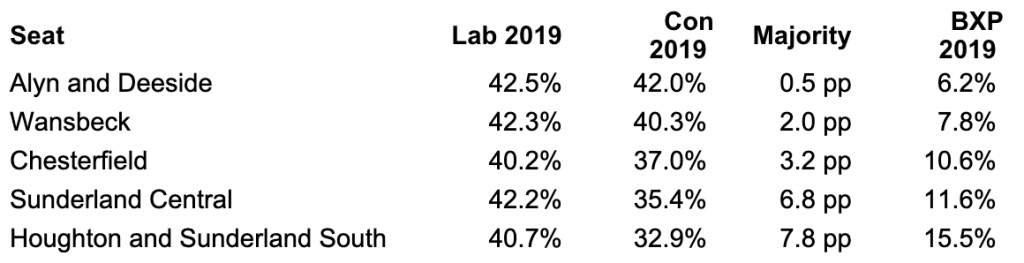

The table below shows the 11 Labour seats where the Con/BXP vote exceeded that of the Lab/Lib Dem/Green vote.

There are two seats – both in and around Barnsley – where the Brexit Party came second and their vote combined with the Tory vote was larger than the Lab/Lib Dem/Green vote. And there are five seats where the Brexit Party vote was five or more points larger than the Labour majority, though the Lab/Lib Dem/Green vote was larger than the Con/BXP vote.

A Progressive Alliance?

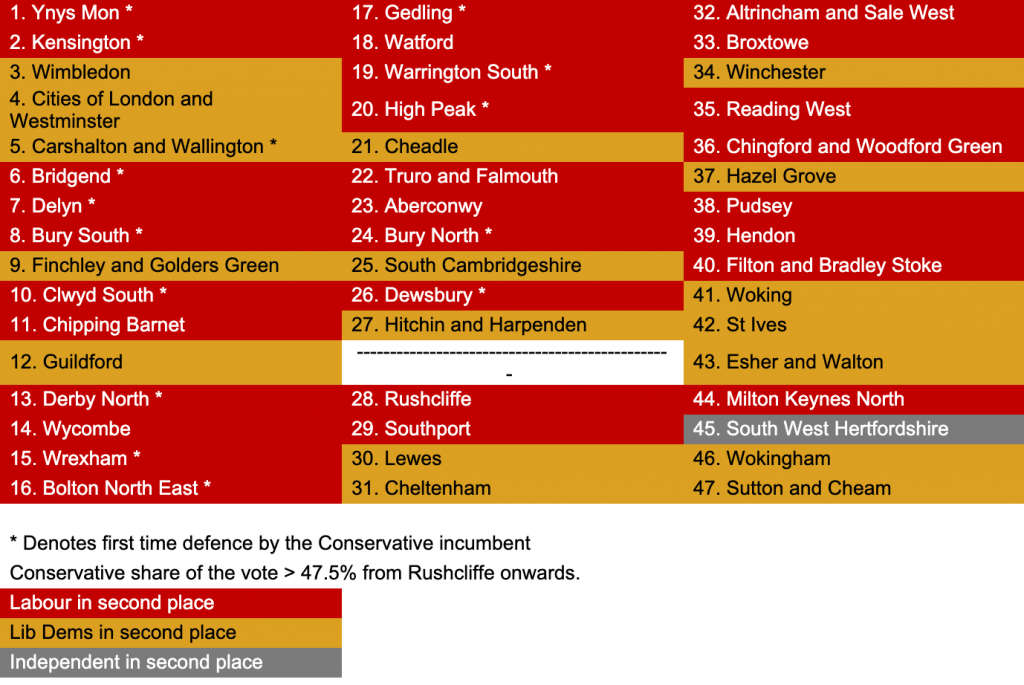

The table below lists the 47 seats where the Lab/Lib Dem/Green/Plaid Cymru vote (and certain others – e.g. Anna Soubry in Broxtowe) was higher than the Con/BXP vote in 2019. It is sorted by the Conservative share of the vote, ranging from 35.5% in Ynys Mon to 49.98% in Sutton and Cheam. The seats are colour coded by the nearest challenger (29 Labour, 17 Lib Dem and 1 Independent)

The location of these seats and the 18 Conservative targets identified earlier can be found in this map. Unsurprisingly the Lib Dem targets are generally in the South East of England. What’s interesting is that with the exception of Dagenham & Rainham and Alyn & Deeside, the Conservative targets are to the north of the Trent and east of the Pennines.

As we have already seen, it is incredibly rare for the Conservatives to lose a seat once they get above 47.5%. The Tories achieved at least that in 20 of these seats in 2019. However, if the Tories do absorb much of the Brexit Party vote (2.1% in 2019), then they would have to be losing votes elsewhere to stand still in the GB share of the vote.

Some of these seats are not straightforward. Ynys Mon is a three-way marginal with Plaid Cymru in third on 28.5%, while there was only 3.5 points between the Lib Dems and Labour in Cities of London and Westminster. And South West Hertfordshire is probably safer for the Tories than the 2019 result suggests given the incumbent David Gauke won 26.0% of the vote as an independent.

There’s also a limit to how far tactical voting can be relied upon. In the recent Airdrie and Shotts by-election, there was a swing to Labour from the Conservatives and Lib Dems. However, the SNP won comfortably with 46.4% of the vote as 3,000 still voted for their first choice unionist party.

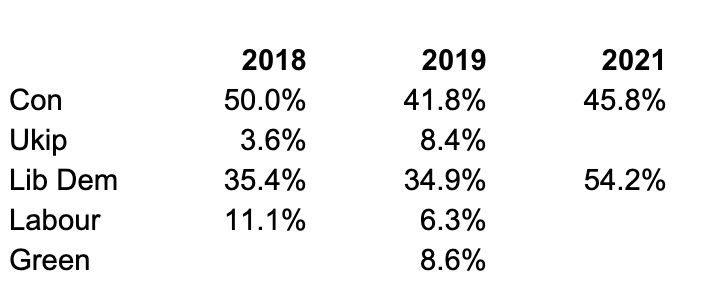

For some time Polly Toynbee has advocated that Labour ought to do a deal with other parties. I live in Woking (seat 41 on the list), which has returned a Conservative MP at every election since it was created in 1950. Generally the Lib Dems have been the closest challenger to the Tories in the last thirty years, but there has usually been a substantial Labour vote.

In the recent local elections for Woking Borough Council, Labour (and the Greens) did not contest the seat of Horsell. The Lib Dems duly secured a 54:46 win to gain the seat from the Tories.

An electoral pact at a general election would obviously be a far bigger deal than what happens at the local level. The possibility of a deal with the Lib Dems was discussed at length in the 1990s, only for Tony Blair to win a landslide for Labour in 1997. Are things so different now that Labour’s best option is to do a deal? I think in terms of the next election, and possibly the one after, the answer is “yes”.

Whether voters in the Labour areas of places like Woking (Sheerwater and Maybury) would vote Lib Dem is questionable. The details could also be tricky: Should Labour deal with Plaid Cymru? What could Labour offer to the Greens? But given that Labour look unlikely to win an outright majority at the next election, I think this is something that they should consider if they think it is worthwhile trying to deny the Conservatives a majority at the next election. In particular, I think they should consider a deal if they see their route to power through places like Wycombe and Woking rather than through regaining the seats lost in 2019.

Tom Leveson Gower

Tom Leveson Gower posts on PB as TLG86