MAYBE BABY: POPULATION POLITICS PART 2

Previously, I examined how conception and maternity rates had changed in England and Wales during the 2010s. Now for the tricky part – should the government seek to alter demographic trends, and if so, why, and how?

In September 2021, the Social Market Foundation (SMF) published a briefing paper titled Baby bust and baby boom: Examining the liberal case for pronatalism. I’d recommend reading it in full as it provides a very good assessment of this subject. The paper assesses the case for pronatalist policies from three perspectives: parents, children, and society/economy.

Parents

For parents, two gaps are analysed: fertility and happiness. On the fertility gap, the SMF report that a 2011 Eurobarometer survey “found that on average women would ideally like to have 2.32 children, and men 2.14”, which is significantly higher than the 1.58 fertility rate recorded in 2019. However, the data are from 2011 and it may be that attitudes have changed since then. Furthermore, the survey asks about the ideal family size. It may be that some people that consider three or more children to be ideal stop after two (or one!).

As for the happiness gap, the paper states that many studies have found parents to be less happy on average than non-parents. I’m not sure how useful such comparisons are as the two groups are not directly comparable. Those without children will include many who didn’t want them. It may be that such people tend to be happier anyway. Children may be testing at times for parents, but it’s impossible to measure the counterfactual of parents not having had kids. Furthermore, the SMF point out that figures are just averages that probably hide considerable variation. Before moving on to children, it’s worth noting that in June 2021 YouGov asked parents if they could turn back time would they have had more, fewer, the same number, or no children at all. While 8% said they would have fewer or no children, 29% said that they would have had more children.

Children

The SMF paper asks, “would children benefit from being born?” What follows is an incredibly deep philosophical discussion. My view on this is broadly neutral. I don’t think future generations are owed life and I’m certainly not

opposed to contraception or abortion. But other than for a very small number of children in the UK, neither do I think that being born is a bad thing.

Society and the economy

Finally, the paper examines whether the economy and, therefore, society would benefit from a higher birth rate. It highlights three ways in which the economy suffers from low fertility rates: a worsening dependency ratio between workers and non-workers, reduced economic demand, and less chance of innovation due to fewer babies being born. The SMF believe the economic case for pronatalist policies is a strong one. However, they note that the challenges of an aging population may result in increased productivity through innovations and acknowledge the argument that we should welcome reduced fertility rates from an environmental perspective. They also state:

[Pronatalism] could also widen the gender pay gap; past SMF analysis shows that female employment rates decline with number of children, while this is not the case for men. More fundamentally, pronatalism could undermine efforts to achieve gender equality and risks shifting the role and status of women back towards “traditional values” that we have gradually been moving away from. A pronatalist policy program, if there is to be one, needs to consider such issues and take steps to mitigate them.

I think there is an unhealthy obsession with wanting men and women to behave in the same way. Why should it matter if a higher fertility rate results in a fall in female employment? If everyone is doing what’s right for them, then we shouldn’t worry. Perhaps there is a case for the government subsidising childcare further. The SMF note that UK has the third highest childcare costs in the OECD (only in Switzerland and New Zealand is it more expensive). However, I’m not sure how much difference it would make to gender differences. Here’s what the SMF say later in the paper about possible pronatalist policies:

Increasing leave entitlements for mothers…seems more likely to make a difference than increasing entitlements for fathers… With mothers in Britain currently entitled to 39 weeks of maternity pay, a substantial increase that moved the country closer to Estonia, Finland or Hungary (offering over three years’ paid leave) or Norway (91 weeks) could plausibly shift the country’s fertility rate.

In Part 1 we saw that there was a possible link between housing costs and the fertility rate. The SMF say:

Households that benefited from the reduction in mortgage costs as a result of the Bank of England lowering its interest rate in 2008-09 were more likely to have children. The effect of the rate cut – which lowered mortgage payments by 42% on average (over £300 a month) for those on adjustable rate mortgages – is credited with raising the birth rate by 7.5%. Thus there is some reason to think policies that significantly lower the cost of housing could boost birth rates, though the evidence is not conclusive.

This does not bode well for the future given that the base interest rate has remained below 1% since the financial crisis. Given inflationary pressures following the pandemic, rates are likely to rise, and it seems reasonable to expect that this may reduce fertility rates further.

What should politicians do and why?

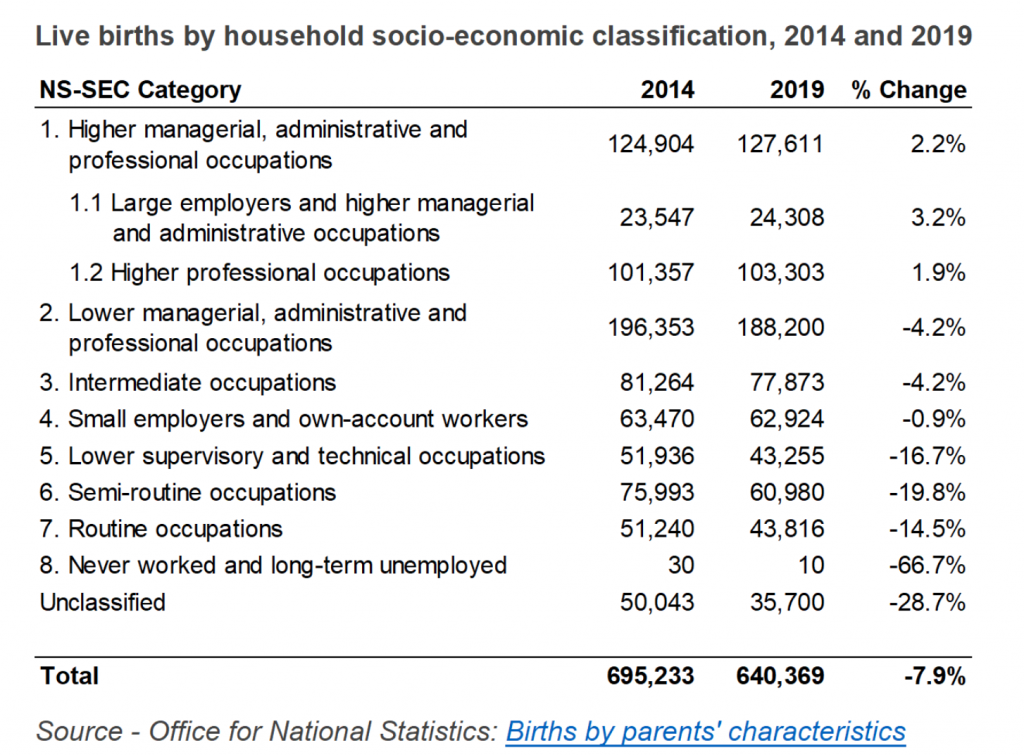

The SMF say that “of all the arguments we have looked at, the economic case for pronatalism is perhaps the strongest and least controversial.” I disagree with this. I think if we want to halt and even reverse declining fertility rates, we should seek to do it for the parents. If the fall in fertility rates was happening simply through choice, then I don’t think it would be right for the government to intervene. People should not feel a duty to have children. But as we saw in Part 1, it is likely that financial considerations have contributed to fewer children being born. Having children is always going to be a decision where sacrifices have to be made irrespective of government policies, but I think it’s entirely reasonable to assess the level of help provided to parents. Anecdotes in articles such as this one in the Guardian give the impression that financial pressures are reducing the fertility rate among those in professional occupations. However, data from the ONS suggests that the decreases in fertility rates between 2014 and 2019 were larger among those in lower supervisory, technical and (semi-) routine occupations.

The SMF argue that instead of pursuing a distinct ‘population strategy’ to increase the birth rate, “the government should convene a cross-departmental working group to examine how different policies affect the birth rate. A House of Lords special inquiry committee on pronatalism should also be formed in 2022.” Whilst this may be useful, I suspect to make any real difference, quite fundamental changes are needed.

Other than building more houses, what else could be done? One option would be to radically alter our taxation system to make it much more like the French system where couples are rewarded for having more children. Obviously, this would require others in society to pay more in tax. As a single man without children, I wouldn’t have a problem with this. However, such changes might not make much difference to those parts of society that have had the largest falls in fertility rates. Perhaps greater subsidies for childcare would make more of a difference. Nevertheless, radically altering the tax system might be worth considering for another reason. As well as potentially increasing fertility rates, it may alter when women have children.

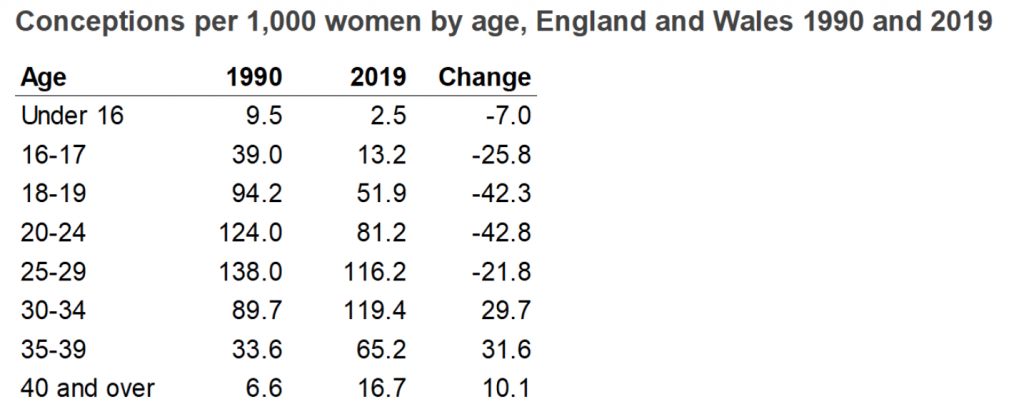

Source – Office for National Statistics: Conceptions in England and Wales

Not only are women having fewer children, but they are also having them later in life. I think there is a case for seeking to reverse this trend. The statistics above show that women very obviously can have children in their late 30s and into their 40s. However, the NHS say that:

Women become less fertile as they get older. One study found that among couples having regular unprotected sex:

- aged 19 to 26 – 92% will conceive after 1 year and 98% after 2 years

- aged 35 to 39 – 82% will conceive after 1 year and 90% after 2 years

Furthermore, on miscarriages the NHS also say that:

The age of the mother has an influence:

- in women under 30, 1 in 10 pregnancies will end in miscarriage

- in women aged 35 to 39, up to 2 in 10 pregnancies will end in miscarriage

These factors likely add to the stress of trying for children and whilst the wonders of IVF help many to conceive, there are no guarantees of success (or NHS funding). The other thing about starting a family later in life is that it reduces the time to have more than one child.

One might argue that having children later in life is beneficial to women from a career perspective, but I’d point out that Margaret Thatcher had her twins at the age of 27, six years before becoming an MP. Of course, society has changed a lot since then. Any policy that seeking to reduce the age at which women have children would require men to play ball, too.

This is obviously a very complicated and sensitive topic. Any policies would need to be carefully considered and fully costed. Is it likely that any politicians would take up this cause? Almost certainly not. This topic has received attention in the press in recent months, but I don’t think it’s an issue that would swing many votes. The reality is that whilst there may be a case to reverse the trend of the last decade, it’s probably more hassle than it’s worth.

Tom Leveson Gower

Tom Leveson Gower posts on PB as TLG86

Support the site New Year appeal